NYSSLS Science Clusters: What They Are and How They Actually Work in the Classroom

At Syzygy Science, I am developing a new series of lab book templates for secondary science courses, including Non-Violent Forensic Science and Regents Physics. Creating meaningful labs requires more than simply addressing what students learn; it involves considering how they are expected to reason, investigate, and demonstrate understanding under NGSS and NYSSLS. The science cluster model is central to this process, yet its practical purpose can be obscured by unfamiliar terminology. This article is the first in a series designed to clarify what clusters are, why they matter, and how they can inform the design of labs that reflect authentic scientific practice.

When teachers first encounter the New York State Science Learning Standards, the concept of science clusters can sometimes feel more confusing than clarifying. While terms like Physical Science, Life Science, Earth and Space Science, and Engineering are familiar, in these standards they signal a genuine shift in how we are asked to teach—and how students are meant to think. To use clusters effectively, it helps to understand what they truly represent and what they do not.

Science clusters, as defined by the New York State Science Learning Standards, are not courses, tracks, or isolated silos. Rather, they serve as disciplinary perspectives that describe the kind of scientific thinking students are engaged in at a particular moment. The objective is not to divide science into separate compartments, but to encourage instruction that reflects the integrated and dynamic nature of scientific knowledge as it is developed and applied.

A common question follows quickly: Are clusters an instructional model? An assessment tool? A curriculum structure?

Clusters are not, by themselves, instructional models, assessment tools, or curriculum structures. Instead, they function most effectively as a framework for planning and reflection—a means of clarifying which scientific domains are engaged during an investigation and for what purpose.

One of the clearest ways to see this is through biology.

Using Biology to See Cross-Cluster Integration

Life Science is frequently taught as a distinct subject. However, nearly every meaningful biological investigation relies on physical mechanisms, environmental context, and engineered methods. The NYSSLS cluster structure makes these interdisciplinary connections explicit rather than leaving them implicit.

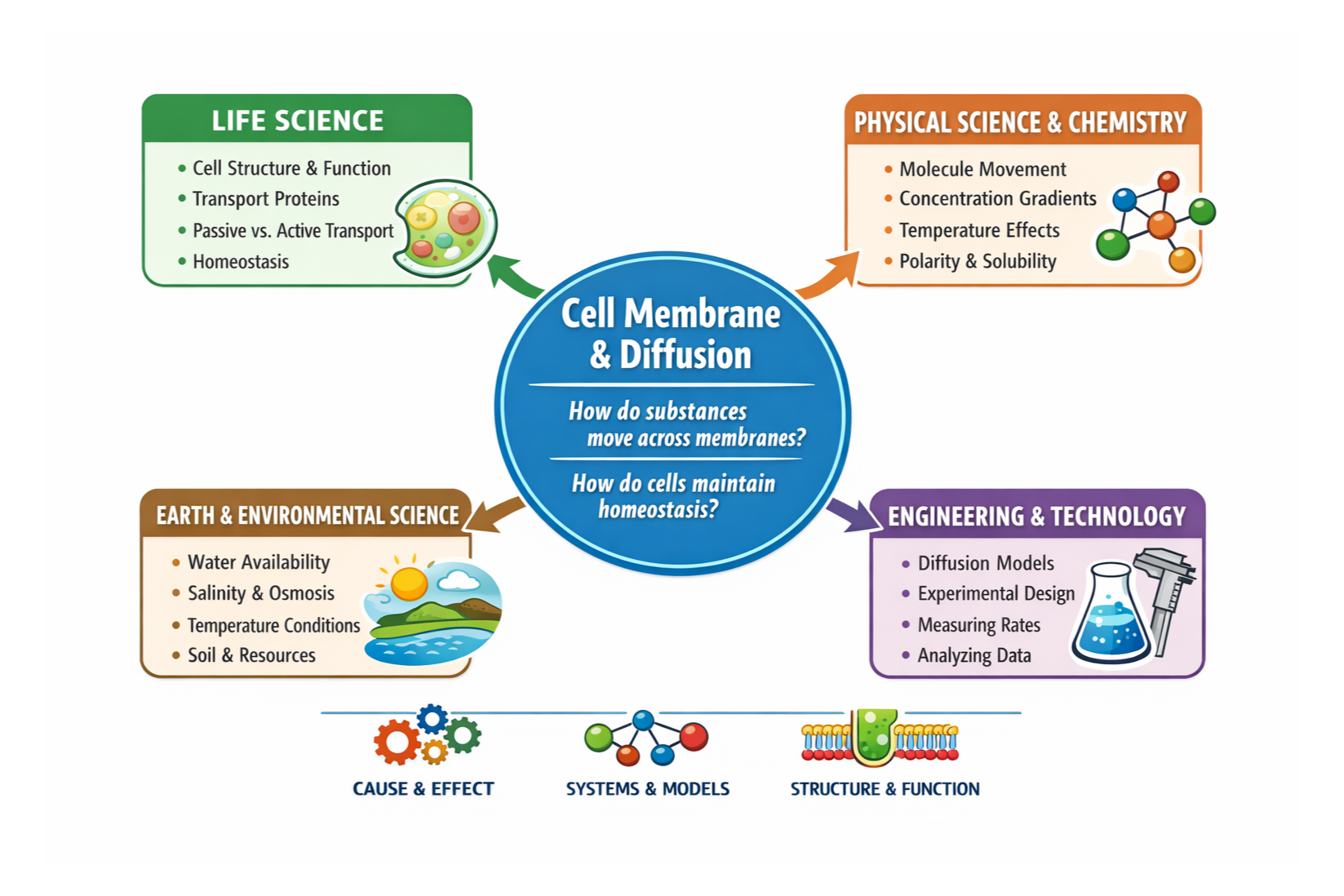

Consider a standard biology topic: cell membranes and diffusion. At first glance, this appears to live squarely within the Life Science cluster. Students study membrane structure, transport proteins, and the role of diffusion in maintaining homeostasis. These are clearly biological ideas.

However, when students are asked why diffusion occurs, the investigation necessarily extends beyond biology. Explaining diffusion requires an understanding of Physical Science concepts such as particle motion, concentration gradients, and temperature effects. Determining which molecules can pass through membranes draws on Chemistry, including properties like polarity and solubility. Modeling diffusion with agar cubes or dialysis tubing engages Engineering and Technology by prompting students to evaluate how well a model represents a biological system. Considering environmental variables—such as salinity, water availability, or temperature—incorporates Earth and Space Science into the analysis.

Studying the cell membrane and diffusion leads naturally to other content areas.

Nothing about the lesson has changed. The question is biological, but the explanation is integrated.

This perspective helps clarify the structure. Life Science anchors the concept, Physical Science explains the mechanisms, Earth and Space Science provides the context, and Engineering offers the tools for investigation. Rather than competing, the clusters work together—each providing a unique lens that enriches students’ understanding.

What the Clusters Are—and What They Are Not

This example highlights a key point that is often overlooked: clusters do not dictate lesson structure. Teachers do not need to “switch clusters” mid-class or ensure all four are present in every unit. Instead, clusters describe the type of scientific reasoning students employ as they work through a problem.

Used this way, clusters serve several important functions:

During lesson planning, they help teachers clarify the scientific grounding of an activity.

During assessment, they help articulate what kinds of reasoning students are demonstrating.

At the curriculum level, they support coherence by showing how investigations build across disciplines rather than remaining isolated.

Clusters do not prescribe pedagogy. They are not a checklist for compliance or an instructional script. Integration is not something teachers add artificially; it is an aspect they recognize and support through intentional design.

Why This Matters

The NYSSLS cluster model reflects a broader shift in science education—from isolated content coverage toward explanation, evidence, and systems thinking. Real scientific problems are not organized by discipline, and effective science instruction reflects that reality. Clusters provide a shared language for describing this integrated approach.

When teachers understand clusters as lenses rather than boxes, biology no longer feels disconnected from chemistry, physics, or Earth science. Investigations become more authentic, reasoning becomes more rigorous, and students gain a clearer picture of how science actually works.

In the next part of this series, we will step back from classroom examples to examine the broader paradigm shift behind the cluster model—why NYSSLS emphasizes integration, scientific practices, and applied reasoning, and what this means for designing labs, units, and entire courses.