Designing for Genuine Inquiry: The Syzygy Cluster Design Model

Science pantomime occurs when students go through the motions of inquiry without engaging in authentic investigation. They follow prescribed steps, complete tables, and arrive at expected answers. Ultimately, when asked what they have learned, many offer little evidence of understanding—sometimes merely repeating answers without comprehending the underlying concepts.

A framework doesn't arrive fully formed. This one started with a forensics class and a question I couldn't stop asking.

A year ago I set out to build three laboratory inquiry books — one for Biology, one for Physics, and one for a course I was calling Nonviolent Forensic Science. The forensics idea came from a frustration with existing materials. Most forensic science curricula lean hard into the sensational. I wanted to teach the science of forensics without glorifying what forensic science is sometimes called to investigate. Blood spatter, toxicology, trace evidence — the science is rich and genuinely compelling on its own terms.

But as I started designing those lessons I ran into a problem that had nothing to do with forensics. I had no consistent model for building an investigation. Every lesson made its own rules. Some were more open than others. Some aligned to NGSS standards, some didn't. If I was going to build something scalable enough to fit real classroom schedules and rigorous enough to produce genuine learning, I needed a framework first.

That question sent me somewhere I didn't entirely anticipate.

Starting With Clusters

I was familiar with how New York State uses the term "cluster" in its science assessments. In the NYSSLS framework, a cluster is a group of data artifacts organized around a specific phenomenon. The cluster presents students with layered evidence and asks them to interpret it, apply concepts, and build explanations across all three NGSS dimensions. It is a sophisticated assessment tool, carefully scaffolded toward a specific Performance Expectation.

I kept asking myself: what would a cluster look like if it wasn't an assessment?

What if the data artifacts weren't selected to scaffold a student toward a predetermined conclusion, but to genuinely open a phenomenon to investigation? What if the student chose the lens and the tools rather than the assessment designer? What if the cluster was the inquiry itself, rather than a measure of whether inquiry had previously occurred?

That question didn't have an obvious answer. So I started following it.

What Genuine Inquiry Actually Requires

Genuine inquiry has specific requirements that most classroom investigations quietly violate.

The phenomenon has to resist easy explanation. Not artificially, but genuinely. A phenomenon a student can explain in thirty seconds without investigating isn't a phenomenon. It's a prompt.

The evidence has to be rich enough to support multiple valid pathways. If there is only one legitimate route through the investigation, students aren't choosing. They're following. I started designing Evidence Packages with up to twenty pieces of evidence, deliberately including material that conflicts, complicates, and occasionally dead-ends. Real scientific data is like that. A student who has never sat with contradictory evidence and had to make a judgment call has not done science. They have filled out a table.

The student has to own the investigative lens and the tools. The NGSS gives us a rich vocabulary for both: Crosscutting Concepts as lenses, Science and Engineering Practices as tools. But in most classrooms these are assigned, not chosen. Paul Andersen of The Wonder of Science put it simply: "Don't kill the wonder and don't hide the practices." Assigning the lens kills the wonder. Assigning the practice hides it. In genuine inquiry, the phenomenon and the evidence tell the student which lens to reach for. The teacher's job is to design conditions rich enough that those choices emerge naturally.

The student also needs a structure for moving through the investigation without being directed toward a conclusion. I settled on a cycle I call ETR-C: Explain your current thinking, Test it against the evidence, Revise it when the evidence pushes back, Communicate it, then start again. The revision step is the critical one. Not adding vocabulary to an unchanged idea, but genuinely rebuilding an explanation when the evidence demands it. That is where the learning lives.

The Assessment Problem

Genuine open inquiry and NGSS Performance Expectations pull in different directions. Open inquiry asks students to choose their own CCC and SEP. Performance Expectations fix them. Open inquiry evaluates reasoning quality. PE assessment evaluates three-dimensional achievement against a specific standard. Open inquiry uses the cluster phenomenon as the context. PE assessment requires a brand new scenario to test whether understanding genuinely transfers.

These are not compatible within a single assessment event. But they are compatible within a single instructional arc, if you keep them clearly separate.

The solution I arrived at is the Breakpoint. The open inquiry of the Syzygy Cluster runs its full course. Then the terrain narrows. The Breakpoint is where the investigation converges onto a specific PE, a specific scenario, and fixed dimensions. The student crosses it independently, without scaffolding, in a context they have never seen. The question it answers is not "did the student follow the investigation?" It is "did the student build understanding durable enough to travel?"

The Openness Problem

As the framework developed I kept returning to the same question: how open is open enough?

Openness is not about removing all structure. It is about removing predetermined conclusions while keeping the conditions for genuine reasoning intact. Syzygy lessons are designed with soft borders. The boundaries between Disciplinary Core Ideas are permeable by design. A student investigating a life science phenomenon might reason their way into earth science or physics. A dead end is not a failure. It is a data point, and learning to recognize one is itself a scientific skill.

Every Syzygy Cluster is built with a PE Constellation, a teacher-facing map of all the Performance Expectations within the DCI that a student might legitimately reach. It is not a fence. It is a map of where genuine inquiry might naturally travel. When a student's work lands on a PE that wasn't part of the lesson plan, that is not a surprise to correct. It is evidence that the inquiry was real.

Where This Stands

I began with a forensics class and a need for a consistent design model. What I arrived at is a framework I did not entirely anticipate when I started, one that has been revised, tested, and revised again. Version 9 of the Syzygy Cluster Design Document will be released shortly, along with a first sample lesson. Both are still in draft form. That feels appropriate. A framework for genuine inquiry should probably not pretend to be finished.

I am also building an app that takes teacher prompts and existing canned labs and converts them into open inquiry models aligned to the Syzygy framework. It is not perfect yet, but it is already producing reliable first draft lessons. If you have a lab you love that doesn't quite meet the inquiry threshold, this is being built with you in mind.

Don't kill the wonder. Don't hide the practices. That is still the inspiration. This framework is my attempt to give teachers the tools to meet it.

NGSS Science Clusters Part III: From Understanding to Building

The first two posts in this series established a key argument: clusters are not isolated subjects but disciplinary lenses connected by Crosscutting Concepts (CCCs) and Science and Engineering Practices (SEPs). Real understanding in science means applying knowledge to explanations, not simply memorizing facts. This post now moves deliberately from defining clusters to the practical—and challenging—work of constructing them for meaningful inquiry.

Understanding and Doing

Any experienced teacher reading about cluster-aligned instruction will feel two things at once. The first is recognition; yes, this is what science should look like. The second is a quieter skepticism: how does this actually work in a room with 28 students and 40 minutes?

That skepticism is justified. Genuine inquiry is slow and nonlinear. For example, a student pursuing a real question about why cells swell in pure water will need chemistry to explain polarity, physics to explain concentration gradients, and engineering when building a model of what they think is happening. None of that fits neatly into a single period, a single discipline, or a single correct answer. This complexity is at the heart of authentic science learning.

The traditional lab sidesteps this complexity by scripting everything. Students follow procedures, record expected results, and confirm what the teacher has already told them. It looks like science, but it isn't. Most teachers who have done this for years already sense something is missing, which points to the fundamental difference cluster-aligned instruction aims to address.

A Cluster is a Guide

The difference between a cluster-aligned investigation and a traditional lab isn't structural; it's intentional. Both can have procedures, data collection, and questions. What separates them is whether students are being led to a predetermined result or genuinely invited to explain something they don't yet understand.

A traditional lab is written around an answer. The phenomenon is chosen because it reliably produces the expected outcome; the procedure efficiently gets students there; and the questions confirm they arrived. There is a place for confirmation in science education, but it isn't inquiry. Students generally know it isn't. They are performing science, not doing it.

A cluster, in this context, is a purposeful grouping of interconnected scientific concepts, practices, and crosscutting themes focused on investigating a phenomenon. Unlike a traditional lab, which is structured around known outcomes, a cluster frames learning around a central, challenging question. The phenomenon selected does not yield to a simple explanation—students must use reasoning to make sense of it. The CCCs and SEPs are not just organizational labels; they are essential tools students draw on as the investigation requires crossing disciplinary boundaries. For example, Cause and effect are fundamental both in biology and physics; Constructing Explanations is needed whether students analyze a cell membrane or a concentration gradient. A cluster prompts students to seek out content because they need it to build an explanation, not simply because the topic appears next on the syllabus.

The Example of Cell Transport

Taught traditionally, cell membrane transport becomes a classification exercise: students learn the mechanisms, memorize the conditions that govern each one, and fill in a chart. The content is covered, but whether it is understood is a different question.

Anchor it differently. Show students three beakers. A red blood cell in salt water shrivels. The same cell in pure water swells until it bursts. In saline at the same concentration as blood, it stays intact. Ask them why.

That question has no vocabulary answer. Students have to reason about what is moving, why it moves, what stops it, and what the cell is trying to accomplish. The biology pulls in physics; particle motion and thermodynamic equilibrium. It pulls in chemistry: polarity, molecular size, and membrane permeability. When students model what they think is happening with a dialysis tube, they are doing engineering, asking how well this physical system represents a biological one, and where the comparison breaks down.

The relevant standards are HS-LS1-2, which models how systems of cells perform essential functions, including material movement, and HS-LS1-3, which focuses on feedback and homeostasis. The disciplinary core idea, LS1.A, tells us that membrane structure determines function; selective permeability is tied to the physical and chemical properties of both the membrane and whatever is trying to cross it.

The DCI gives students the content they need. The SEPs give them a method for generating and using evidence. The CCCs provide a way to organize reasoning when the investigation crosses disciplinary boundaries. A student working through this isn't following a predetermined path. They are choosing which question to pursue, which CCC lens is most useful at a given moment, and which SEP helps them generate the evidence they need. The teacher's job is to design an experience in which those choices are real, and the investigation holds together regardless of which direction the reasoning takes them.

The Design Problem

Building investigations this way is real work. For a single topic, it is demanding; across a full course, it is unsustainable without a framework to work from. Not a script, but a set of design questions a teacher can return to consistently.

What is the phenomenon, and what genuine questions does it raise? Which discipline anchors the investigation, and which others will explanation naturally draw in? Which CCCs will students need as reasoning tools? Which SEPs will generate the evidence required for a complete explanation? What does a finished explanation look like when a student has produced it?

Answering those questions across every topic in a course is where teacher creativity and the demands of the standards must meet. Most teachers navigate this alone, rebuilding the design logic from scratch each time. A design template doesn't solve that problem completely, but it gives it some shape.

Time

Forty minutes is not enough time for genuine inquiry—neither is ninety. Inquiry does not resolve in a single sitting; it accumulates across sessions, each one building on the last without definitive closure.

Students will resist this. They want the right answer; they have been trained to believe that is what school is for. But inquiry is more about the quality of the question than the correctness of the answer, and content knowledge in this model is something earned through the process of explanation, not distributed in advance as scientific trivia. Knowledge that a student needs to answer a question they are genuinely asking tends to stick. Knowledge handed over before the question exists tends not to.

Designing for this requires care. An open-ended investigation without structure produces frustration, not understanding. The goal is an experience where real thinking is both possible and necessary, where content becomes useful rather than merely preparatory, and where not having the answer yet is a normal condition—not a sign that something has gone wrong.

The standards describe what that learning should look like. Teachers bring creativity, subject knowledge, and an instinct for what their students need. What is often missing is the structure that holds those things together. That is the work Syzygy Science is taking on: a design template that brings standards, genuine student experience, and teacher creativity into alignment, not to make inquiry tidy, but to make it teachable. The mess is part of it. The template is about building a space that can hold that mess without losing the thread.

---

If you want to work through the design process before the template is ready, or have questions about cluster-aligned instruction for your own courses, please make a comment below. This series continues.

NGSS Science Clusters Part II: The Paradigm Shift Behind the Clusters

Why Science Class Feels Different Now

Teachers quickly sense that science class feels different. Lessons run longer, labs are less predictable, and students who can recite facts often struggle to explain real phenomena. Familiar rubrics built around arriving at the “correct answer” no longer seem to fit the work students are being asked to do. What’s emerging is more than a curriculum update—it’s a shift in how science learning itself is defined.

The New York State Science Learning Standards (NYSSLS) reflect this change. It’s not simply a matter of new language or reorganized content. Students are now expected to use ideas, demonstrate understanding through reasoning, and show rigor through explanation and application. The cluster model helps clarify these expectations by making the kind of thinking students are asked to do more visible.

This shift becomes most apparent not when teaching new material, but when revisiting topics that are already familiar.

From Coverage to Understanding: What’s Really Changed?

Consider a classic example: cell membranes and diffusion. For years, student success meant defining key terms, memorizing steps, and filling in diagrams. Mastery was largely about recall.

Under current expectations, that is no longer enough.

Explaining diffusion now requires students to reason about motion, energy, and evidence. They are asked to predict outcomes, explain mechanisms, and apply ideas to new situations. Struggle in this context is not a failure; it is evidence that memorization alone no longer satisfies the definition of understanding.

The real change is this: students must show understanding, not simply possess information.

This is where science clusters matter. When students struggle despite knowing the content, the issue is rarely a lack of knowledge. It is a shift in the kind of thinking being required. The cluster model helps teachers recognize and name that shift—from recalling facts to reasoning, modeling, and explaining. Rather than adding hurdles, clusters provide a shared language for what counts as understanding in today’s science classroom.

The Cluster Model: Clarifying New Expectations

A central feature of this shift is the move away from content coverage as the primary measure of progress. Pacing guides and topic lists once provided structure and reassurance. Progress meant completed chapters and finished labs.

NYSSLS redefines rigor. Students are expected to analyze data, construct explanations, evaluate evidence, and revise their thinking over time. This work takes longer and unfolds less predictably, because the old markers of success no longer apply. For teachers, this often means rethinking planning, grading, and even what it means for a lesson to be “successful.”

This discomfort is real. Lessons may end without tidy conclusions. Grading may feel less straightforward. But these are signs that the instructional focus has shifted—from delivering content to developing reasoning.

Clusters help anchor this transition. By naming the kinds of thinking students are engaged in—explanation, analysis, modeling—they give teachers and students a clearer roadmap. Change feels more manageable when expectations are explicit.

This shift does not diminish the importance of scientific knowledge or teaching expertise. It reframes how knowledge functions in the learning process.

Integrating Disciplines: Science Without Borders

Traditional disciplinary boundaries—biology, chemistry, physics—once made teaching and assessment easier. They aligned with textbooks, simplified planning, and supported familiar instructional routines.

As explanation moves to the center, however, those boundaries begin to blur. Real-world phenomena do not separate neatly into disciplines, and neither do the standards that now guide science instruction.

Explaining systems often requires ideas from multiple fields: physics within biology, chemistry within environmental science. This integration makes understanding more authentic, but also more demanding. The cluster model does not force this integration; it makes it visible and valued.

Labs and Evidence: Learning Science by Doing Science

Nowhere is this shift more evident than in laboratory work. Traditional labs often rewarded procedural accuracy and confirmation of expected results. Rigor was associated with correctness and completion.

Today, labs function as evidence-generating systems. Students collect data, interpret results, justify claims, and confront uncertainty. Rigor is redefined as interpretation, justification, and reasoning under imperfect conditions—much closer to how scientific knowledge is actually built.

This change is challenging, but it aligns laboratory work with the goals of the standards and with the practice of science itself.

Rethinking Rigor: Redefining Success in Science

Assessment is often where uncertainty lingers. Core knowledge still matters, but it is no longer the endpoint. Understanding is demonstrated through application—using knowledge to explain, predict, and solve.

Performance expectations now emphasize applying ideas and justifying conclusions. Success means showing how facts function within an explanation, not simply recalling them. Assessment values process alongside product, reasoning alongside results.

Clusters play an important role here by clarifying the type of thinking being assessed. They help teachers design tasks that align instruction, investigation, and evaluation. By making expectations explicit, clusters reduce ambiguity while raising the bar for meaningful learning.

Applied Courses: Ahead of the Curve

Applied science courses—such as forensics, environmental science, or engineering—often begin with real problems and messy data. These courses demand integration, explanation, and evidence from the start, and in doing so have long modeled the kind of learning the standards now emphasize.

The cluster model does not constrain these courses; it helps articulate why they are rigorous and how their practices translate across the science curriculum.

Looking Ahead: Designing for Deeper Learning

Understanding this shift is only the first step. The next challenge is design—how curriculum materials, lab structures, and instructional tools can consistently and sustainably support this kind of learning.

At Syzygy Science, this work is taking shape through the development of cluster-aligned design templates and a growing set of lab experiences for non-violent forensic science, biology, and physics. These tools are intended to make scientific thinking visible, support evidence-first investigations, and help teachers navigate the standards with confidence.

In the final part of this series, we’ll turn directly to that design work: how intentional structure can support deeper learning without returning to coverage-based models, and how clusters can serve as a foundation for coherent, practice-centered science instruction.

NYSSLS Science Clusters: What They Are and How They Actually Work in the Classroom

At Syzygy Science, I am developing a new series of lab book templates for secondary science courses, including Non-Violent Forensic Science and Regents Physics. Creating meaningful labs requires more than simply addressing what students learn; it involves considering how they are expected to reason, investigate, and demonstrate understanding under NGSS and NYSSLS. The science cluster model is central to this process, yet its practical purpose can be obscured by unfamiliar terminology. This article is the first in a series designed to clarify what clusters are, why they matter, and how they can inform the design of labs that reflect authentic scientific practice.

When teachers first encounter the New York State Science Learning Standards, the concept of science clusters can sometimes feel more confusing than clarifying. While terms like Physical Science, Life Science, Earth and Space Science, and Engineering are familiar, in these standards they signal a genuine shift in how we are asked to teach—and how students are meant to think. To use clusters effectively, it helps to understand what they truly represent and what they do not.

Science clusters, as defined by the New York State Science Learning Standards, are not courses, tracks, or isolated silos. Rather, they serve as disciplinary perspectives that describe the kind of scientific thinking students are engaged in at a particular moment. The objective is not to divide science into separate compartments, but to encourage instruction that reflects the integrated and dynamic nature of scientific knowledge as it is developed and applied.

A common question follows quickly: Are clusters an instructional model? An assessment tool? A curriculum structure?

Clusters are not, by themselves, instructional models, assessment tools, or curriculum structures. Instead, they function most effectively as a framework for planning and reflection—a means of clarifying which scientific domains are engaged during an investigation and for what purpose.

One of the clearest ways to see this is through biology.

Using Biology to See Cross-Cluster Integration

Life Science is frequently taught as a distinct subject. However, nearly every meaningful biological investigation relies on physical mechanisms, environmental context, and engineered methods. The NYSSLS cluster structure makes these interdisciplinary connections explicit rather than leaving them implicit.

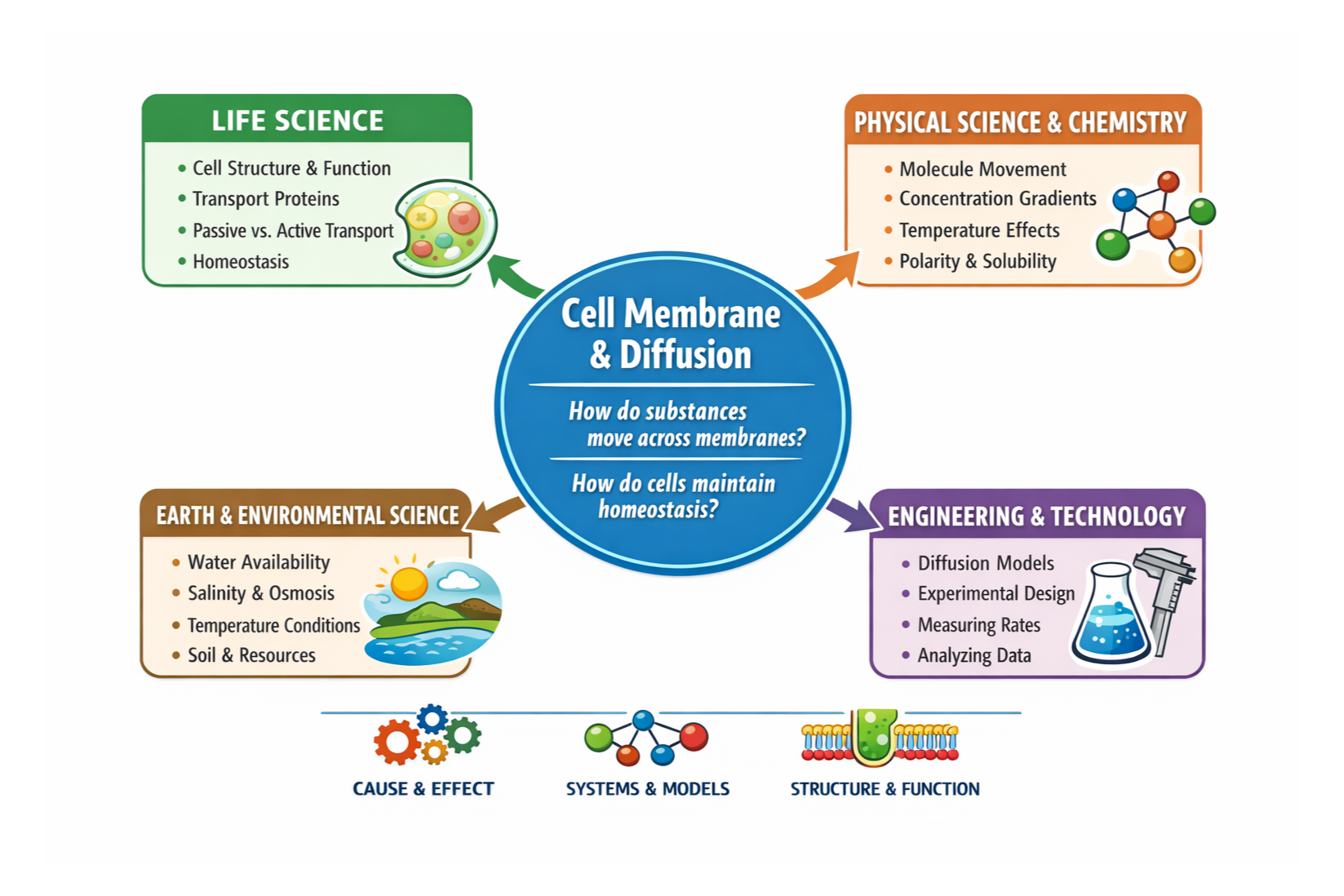

Consider a standard biology topic: cell membranes and diffusion. At first glance, this appears to live squarely within the Life Science cluster. Students study membrane structure, transport proteins, and the role of diffusion in maintaining homeostasis. These are clearly biological ideas.

However, when students are asked why diffusion occurs, the investigation necessarily extends beyond biology. Explaining diffusion requires an understanding of Physical Science concepts such as particle motion, concentration gradients, and temperature effects. Determining which molecules can pass through membranes draws on Chemistry, including properties like polarity and solubility. Modeling diffusion with agar cubes or dialysis tubing engages Engineering and Technology by prompting students to evaluate how well a model represents a biological system. Considering environmental variables—such as salinity, water availability, or temperature—incorporates Earth and Space Science into the analysis.

Studying the cell membrane and diffusion leads naturally to other content areas.

Nothing about the lesson has changed. The question is biological, but the explanation is integrated.

This perspective helps clarify the structure. Life Science anchors the concept, Physical Science explains the mechanisms, Earth and Space Science provides the context, and Engineering offers the tools for investigation. Rather than competing, the clusters work together—each providing a unique lens that enriches students’ understanding.

What the Clusters Are—and What They Are Not

This example highlights a key point that is often overlooked: clusters do not dictate lesson structure. Teachers do not need to “switch clusters” mid-class or ensure all four are present in every unit. Instead, clusters describe the type of scientific reasoning students employ as they work through a problem.

Used this way, clusters serve several important functions:

During lesson planning, they help teachers clarify the scientific grounding of an activity.

During assessment, they help articulate what kinds of reasoning students are demonstrating.

At the curriculum level, they support coherence by showing how investigations build across disciplines rather than remaining isolated.

Clusters do not prescribe pedagogy. They are not a checklist for compliance or an instructional script. Integration is not something teachers add artificially; it is an aspect they recognize and support through intentional design.

Why This Matters

The NYSSLS cluster model reflects a broader shift in science education—from isolated content coverage toward explanation, evidence, and systems thinking. Real scientific problems are not organized by discipline, and effective science instruction reflects that reality. Clusters provide a shared language for describing this integrated approach.

When teachers understand clusters as lenses rather than boxes, biology no longer feels disconnected from chemistry, physics, or Earth science. Investigations become more authentic, reasoning becomes more rigorous, and students gain a clearer picture of how science actually works.

In the next part of this series, we will step back from classroom examples to examine the broader paradigm shift behind the cluster model—why NYSSLS emphasizes integration, scientific practices, and applied reasoning, and what this means for designing labs, units, and entire courses.

Evidence First: A Non-Violent Approach to Forensic Science Education

I am beginning my next curriculum project, a non-violent forensic science curriculum, after teaching forensics for the first time during the 2024–25 school year. Sharing the classroom with students who were curious, creative, and sometimes apprehensive reminded me that what we teach is as much about people as it is about science. While the subject naturally engages students, I found that many existing resources relied on dramatization and sensational details rather than the science itself. My goal became to design a course where student interest is driven by evidence, uncertainty, and reasoning—not by shock or spectacle. This required rethinking how violence, narrative, and human elements are presented in the classroom. The result is an approach that treats forensic science as applied science first, allowing narrative to emerge from analysis rather than lead it.

Non-Violent Forensics: Teaching the Science Without the Sensation

Forensic science occupies a complicated space in schools. I’ve seen the spark in students’ eyes when they start connecting classroom concepts to real-world mysteries, but I’ve also watched them hesitate when faced with graphic or sensationalized content. It is one of the most engaging applications of biology, chemistry, and physics available to students, yet much of the curriculum borrows its tone from television and true-crime media. Violence and dramatization are often treated as essential features rather than contextual realities. Teachers must balance student curiosity, institutional caution, and the responsibility to teach real science effectively.

A non-violent forensic science curriculum does not avoid crime, nor does it soften the science. Instead, it makes a deliberate shift in emphasis—from violent acts to the scientific analysis of evidence. The focus shifts from who was harmed to what patterns exist, what data can be collected, and what explanations are supported by that data. In this model, a crime scene functions as a constrained system for investigation, not as a narrative built around suffering.

This shift matters because much of what is marketed as forensic science was not designed for classrooms. Many resources assume mature audiences, embed science within storytelling, and rely on shock value to maintain interest. I’ve spent hours poring over resources, wrestling with what’s appropriate or meaningful for my students. Teachers are often left to edit content on the fly, define boundaries without guidance, and decide what is “too much” in isolation. The result is inconsistency and, in many cases, avoidance of otherwise valuable scientific investigations.

Forensic science works best in schools when it is treated as applied science, not as a genre of crime. Motion, forces, diffusion, material transfer, and system interactions become the objects of study. Evidence is compelling because it reveals how systems behave under specific conditions, not because it is linked to dramatic events. Questions shift accordingly: What variables influenced this pattern? How reliable is the data? What alternative explanations are possible?

Violence remains part of the real-world context, but it is not the instructional focus. A non-sensational approach acknowledges harm without centering it. System-based investigations—such as illegal chemical disposal, arson framed as property damage, or theft—generate authentic forensic evidence without relying on bodily injury or trauma. Human elements are present but are treated analytically rather than narratively. Suspect profiles function as evidence-based constraints, not as dramatic biographies, and conclusions are framed probabilistically.

This approach also applies to student-created investigations. In professional forensic work, narrative does not initiate analysis—it emerges from it. When students design their own scenarios, I encourage them to think like scientists first, not storytellers. They begin with a scientific objective and a set of defined evidence types. Narrative appears only after evidence is examined, as competing explanations are tested against the data. Creativity is intentionally constrained so that students design analyzable systems rather than stories.

When forensic science is taught this way, it no longer depends on spectacle to sustain interest. Students engage with uncertainty, evidence, and explanation—the same intellectual work that defines science across disciplines. A non-violent forensic science curriculum is not about denying reality; it is about teaching students to engage with it responsibly, rigorously, and with intention.

The Materials Gap

Wonder is the spark that lights the way to genuine, lifelong learning—igniting curiosity that endures long after the bell rings. Yet too often that spark fades because the tools teachers need to sustain inquiry simply aren’t there. National reviews show the depth of the problem: of the science programs EdReports has evaluated, only 17 percent meet expectations for NGSS alignment while 69 percent fall short. A separate survey revealed 96 percent of teachers value standards‑aligned materials, but only 37 percent believe they have them.

This disconnect leaves educators stitching together handouts at midnight and students drifting through disconnected activities that never build toward mastery of the three NGSS dimensions. Science and Engineering Practices (SEPs) become warm‑up tasks, Crosscutting Concepts (CCCs) are too often treated as side notes, and the story of science is lost in the shuffle.

Syzygy Science is closing that gap by designing resources that put the framework—not the filler—first. Every forthcoming unit and lab begins with a real‑world phenomenon, then threads SEPs and CCCs through each investigation so students use the practices to make sense of concepts in context. Our August Biology Lab Manual (30 ready‑to‑teach labs) pairs, for example, protein‑folding models with the CCC pattern of structure and function; our “Living Rivers” project asks students to build and iterate water‑quality models, rooting data analysis and systems thinking in their own watershed.

Because time is a teacher’s scarcest resource, each lesson is field‑tested for a 15‑minute prep window, with formative prompts already mapped to the relevant practice and concept. The result is continuity that survives beyond a single “wow” moment and cultivates durable scientific habits of mind.

If your curriculum cupboard feels bare, join our pilot list or download the first sample lab next month. Let’s replace the materials gap with materials that work.

A New Chapter at Syzygy Science: Reliable Resources You Can Trust

It all begins with an idea.

At Syzygy Science, we’ve always believed in bringing real-world science into classrooms. Today, we’re excited to launch a new site—and a new era—that makes that mission even more tangible.

This site refresh isn’t just a new coat of paint. It’s a reflection of where we’re going: deeper into curriculum development, stronger in our partnerships, and more committed than ever to providing teachers with what they need to teach science effectively.

We’re proud to introduce two main offerings that will shape Syzygy’s next chapter:

Curriculum Services: Custom curriculum writing and NGSS-aligned support for districts, nonprofits, and mission-driven companies who want to see their educational ideas make it to the classroom.

NGSS Resource Library: A growing collection of ready-to-teach lab books, designed with clarity, ethical care, and explicit standard alignment in mind.

We’re starting strong with three cornerstone products, all in development:

A Non-Violent Forensics Curriculum

Investigations that center healing, critical thinking, and scientific rigor—without the gore or sensationalism.NGSS Biology Lab Book

Thirty labs that tie life science practices to real phenomena, step-by-step, with teacher support built in.NGSS Physics Lab Book

Hands-on activities for motion, energy, and systems thinking—crafted to support inquiry and alignment in tandem.

These projects are more than just resources; they are a valuable asset. They’re a promise: that science education can be rigorous, relevant, and responsive to the real world in which students live.

We look forward to sharing more in the coming months. Stay tuned for curriculum previews, lab prototypes, and behind-the-scenes glimpses into how these resources are built.

If you’re a district, school, or organization looking to bring your instructional ideas to life—or just a curious teacher ready for new tools—we’d love to talk.

Here’s to building what science education can be.

—The Syzygy Science Team